The City of Vancouver just announced that it will lease land to private developers in hopes of creating more affordable rental housing in the City. This is part of a broader set of tax breaks and other incentives that aims to get developers to build more affordable housing in Vancouver.

Plans like these are pretty standard in North American cities: they aim to use municipal dollars and municipal policies (like tax regulations and zoning) in hopes of getting developers to create “below-market housing.” Developers usually won’t build cheap rental housing themselves, because it’s more profitable to build expensive rental or condos. In this case, the new units probably won’t be affordable to people living in poverty even if they’re “below market,” since past developments have cost as much as $2000 for a 2-bedroom apartment. Worse, these new developments often promote gentrification, as existing tenants are forced out for renovations (known as renovictions) and the new, swanky, “affordable” units are affordable for yuppies. Observers have complained that:

Plans like these are pretty standard in North American cities: they aim to use municipal dollars and municipal policies (like tax regulations and zoning) in hopes of getting developers to create “below-market housing.” Developers usually won’t build cheap rental housing themselves, because it’s more profitable to build expensive rental or condos. In this case, the new units probably won’t be affordable to people living in poverty even if they’re “below market,” since past developments have cost as much as $2000 for a 2-bedroom apartment. Worse, these new developments often promote gentrification, as existing tenants are forced out for renovations (known as renovictions) and the new, swanky, “affordable” units are affordable for yuppies. Observers have complained that:

The city grants permits for renoviction and demolition almost every day and is giving no hint that it will change its “revitalization” agenda for the city’s most affordable areas… Vision has failed time and time again because they continue to call on the private development industry to solve the affordability crisis.

But Vancouver actually has a history of far more creative, grassroots, and affordable housing creation. In the 1970s and 80s, East Vancouver residents organized to create housing that met the needs of existing residents.

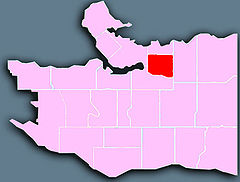

In the 1960s, the Strathcona Area of Vancouver (in East Van) was slated for “redevelopment.” The City of Vancouver had decided that the working-class, primarily Asian neighbourhood was a “blight” and that the City should create public housing projects.

So it began expropriating people’s houses and bulldozing them as part of its “Urban Renewal” plans. In the first phase alone, an estimated 860 residents were displaced–the majority were of Chinese descent. This wasn’t a coincidence, as Asian people and other people of colour were (and often still are) conceived as part of social and economic decay. Nowadays, the City pays developers to “revitalize neighbourhoods” instead. Developers usually won’t build anything unless they can expect a whopping 20% profit margin, so cities like Vancouver are basically paying developers to make huge profits evicting and displacing people.

Strathcona area residents organized themselves and fought back. As part of a whole network of grassroots actions, campaigns, and institutions, they formed SPOTA, the Strathcona Property Owners and Tenants Association, as a way to pressure the City to stop the evictions. SPOTA also became a vehicle to propose and create alternative housing developments that were envisioned and developed by the residents themselves. They created and disseminated their own literature, they had a structure of block captains to organize every city block of Strathcona, they held multilingual meetings with translators, and they used a whole array of protests, lobbying, direct actions, dinners, and other strategies to stop (many of) the evictions and create alternative models of affordable housing that would meet the needs of the people actually living in the neighbourhood.

Strathcona area residents organized themselves and fought back. As part of a whole network of grassroots actions, campaigns, and institutions, they formed SPOTA, the Strathcona Property Owners and Tenants Association, as a way to pressure the City to stop the evictions. SPOTA also became a vehicle to propose and create alternative housing developments that were envisioned and developed by the residents themselves. They created and disseminated their own literature, they had a structure of block captains to organize every city block of Strathcona, they held multilingual meetings with translators, and they used a whole array of protests, lobbying, direct actions, dinners, and other strategies to stop (many of) the evictions and create alternative models of affordable housing that would meet the needs of the people actually living in the neighbourhood.

In the 70s and 80s, SPOTA helped envision, fund and build projects like the Mau Dan Gardens Housing Cooperative, along with Strathcona Area Housing Society (SAHS).

In the 70s and 80s, SPOTA helped envision, fund and build projects like the Mau Dan Gardens Housing Cooperative, along with Strathcona Area Housing Society (SAHS).

These kinds of housing alternatives have major advantages over City-owned and privately-owned developments. First of all, the cooperative structure means that residents themselves participate in the governance and decision-making of the housing. Secondly, they’re insulated from the whims of developers and right-wing governments. Even if a progressive municipality builds a bunch of City housing, it can be sold off by a right-wing regime a decade later (or leased out to private developers, like Vancouver is doing now). Finally, when communities partner with non-profit developers, it cuts private developers (and their 20% margins) out of the picture.

This non-profit cooperative model was never perfect. Some of these cooperatives have since closed down, for a variety of reasons. And some of their major sources of money (such as funding and financing from the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation) have dried up. But grassroots cooperative housing had major advantages over both public and private developers, and they could be happening again in Vancouver. Here are some concrete things the City could (and should) be doing differently:

– Provide funding for existing residents to create housing solutions that actually work for them. SPOTA and SAHS were organized by residents themselves, and it would be easy for non-profit-sector housing to become a new force of gentrification if it isn’t directly accountable to marginalized communities. Existing residents already know what kind of housing they need, and municipal governments can provide financial resources, technical expertise, and the same slew of incentives they’re currently offering to private developers.

– Create and strengthen non-profit developers, non-profit construction companies, and non-profit financing. Here’s how the status quo of housing development works: if the City hires a private developer, they lose 20-30% to profit margins. If they hire a construction company directly instead, they lose 10-15% to profit margins, and another 5-10% to banks (since they usually need financing). At each step of the day, housing development (whether renovation or construction) is made way more expensive because all these private interests are profiting. If the City helped create non-profit alternatives, they could collaborate with them without getting exploited, and cut private profit out of the picture.

– Help form housing co-operatives, lease City land to them, help them secure low-interest financing (and grants and funding from BC Housing), and help them build or renovate housing at low cost (non-profit construction). The City already owns a bunch of land (which it’s about to hand over to private developers), and it could collaborate with residents instead of renovicting.

This might sound pretty grand, but these kinds of things can be pursued on a whole variety of different scales, in different places, with different timelines. For example, the City could partner with credit unions like Vancity to get low-interest financing, use that money to buy houses that are already tenanted, and turn them over to a Community Land Trust (a non-profit housing entity). In many cases, even given current over-inflated housing prices, the CLT would be able to lease the houses back to the tenants at the same price as they currently pay in rent (or rent them back for cheaper). No big subsidies, no evictions, no new building. How? By cutting profit out of the picture: no private developers, landlords, or banks.

In fact, these non-profit housing initiatives don’t even need the City of Vancouver’s “Vision” to move forward, at least not necessarily: they could be spearheaded by existing community groups, as they initially were in Strathcona a few decades ago (although the municipality’s money, zoning power, tax breaks, and bureaucratic expertise would certainly help).

None of these alternatives require a ton of government money, so the City of Vancouver wouldn’t have to increase taxes on developers or property owners (not that they shouldn’t, but that’s a different story). In the current neoliberal age, where cities are terrified of raising taxes and pander to private developers in an attempt to attract capital, these kinds of alternatives can help stem the tide of gentrification, privatization, and displacement that are sweeping cities all over the world. These non-profit models won’t solve these problems, but they’re actually possible right now, without changes to legislation or policy, or a massive influx of money, or any other big obstacles that tend to stymie affordable housing. But as the City has clearly shown, these alternatives won’t happen on their own: they’ll likely require creative, well-organized, grassroots action. Otherwise, the City’s “Vision” is clear: public-private partnerships, renovictions, displacement, and gentrification.